Propulsion Physics: Motors & Propellers

CRITICAL The propulsion system is the physical interface between the flight controller's digital commands and the atmosphere. A mismatch here cannot be fixed by PID tuning. This guide deconstructs the electromechanical physics of the drivetrain to allow for calculated, not guessed, component selection.

1. The Electromechanical Core: Brushless Motor Theory

Modern drones exclusively use Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM), commonly referred to as Brushless DC (BLDC) motors. Unlike brushed motors which use mechanical commutators (creating friction and noise), BLDC motors shift the complexity of commutation to the Electronic Speed Controller (ESC).

1.1 Inrunner vs. Outrunner Architecture

- Inrunner: The rotor spins inside the stator. Common in RC cars or ducted fans. High RPM, low torque.

- Outrunner: The rotor (the "bell" with magnets) spins around the outside of the stator.

- The Physics Advantage: Torque (tau) is the product of Force (F) and Radius (r). By placing the magnets on the outer perimeter, outrunners maximize the lever arm (r) for a given motor volume. This allows them to generate the massive torque required to swing large propellers directly, without the weight and failure points of a reduction gearbox.

1.2 The Motor Constants: Beyond the Marketing

To predict performance, we must look beyond the box art and understand the three intrinsic motor constants.

The Velocity Constant (Kv)

Defined as the theoretical RPM per Volt under no load (RPM ~= Kv * V).

- The Mechanism: Kv is determined by the Back-EMF. As the motor spins, it acts as a generator, creating a voltage that opposes the battery. The motor stops accelerating when the Back-EMF equals the battery voltage.

- Winding Physics: Fewer turns of thicker wire = Low Resistance = Low Back-EMF = High Kv.

- Application: High Kv motors are built for speed but require huge current to produce torque.

The Torque Constant (Kt)

This is the metric that matters for heavy lift and crisp handling. It describes the torque produced per Ampere of current (Nm/A).

-

The Inverse Law: There is a rigid physical relationship between Speed and Torque. You cannot increase one without decreasing the other.

Kt ~= 9.55 / Kv -

Implication: A 2700Kv motor has inherently low torque per amp. To spin a heavy prop, it must draw massive current, generating waste heat (I²R losses). A 1700Kv motor produces the same torque with far less current, making it the correct choice for heavy propellers.

The Motor Constant (Km)

The "Efficiency Truth." Km defines the torque produced for a given amount of waste heat.

- Significance: Unlike Kv, which changes with winding turns, Km is constant for a specific stator size and magnet configuration. A larger stator or higher-grade magnets will increase Km, indicating a motor that can produce more torque with less waste heat.

2. Stator Geometry & Magnetic Flux

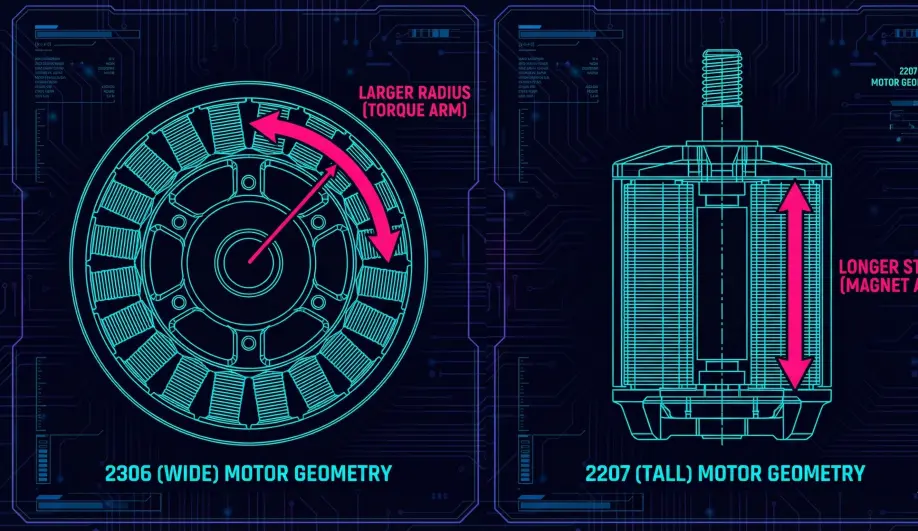

Motor size is standardized (e.g., 2306 = 23mm width, 6mm height). However, the Aspect Ratio of the stator fundamentally changes the power delivery feel.

2.1 Wide Stator (2306) vs. Tall Stator (2207)

Both motors have roughly the same stator volume (~2500 mm³), but they fly differently.

-

Wide Stator (2306):

- Physics: The magnetic interaction occurs further from the center axis. This larger radius increases the instantaneous torque leverage.

- Cooling: Larger top/bottom surface area allows for better convective cooling from the prop wash.

- Flight Feel: "Smooth" and "Linear." Preferred by Freestyle pilots who want consistent power across the throttle range.

-

Tall Stator (2207):

- Physics: Increased surface area along the vertical axis (longer magnets).

- Performance: Higher magnetic flux interaction area typically yields more "low-end grunt" or "snap."

- Flight Feel: "Responsive" and "Aggressive." Preferred by Racers who need to change RPM instantly to corner at high speeds.

2.2 Stator Laminations

The stator is not solid iron; it is a stack of thin steel sheets.

- Eddy Currents: Rapidly changing magnetic fields induce rogue currents in the iron core, creating heat.

- Lamination Thickness: Thinner laminations (0.15mm vs 0.2mm) reduce these eddy currents. High-end motors use thinner laminations to improve efficiency at high RPM.

3. Propeller Aerodynamics: The Airscrew

The propeller converts rotational torque into aerodynamic thrust. This is a fluid dynamics problem governed by Blade Element Momentum Theory.

3.1 Diameter (D)

Thrust scales with the fourth power of diameter (Thrust is proportional to D^4).

- The Scale Effect: Increasing prop size from 5" to 6" doesn't just add "a little" thrust; it drastically increases the disk area and the air mass moved.

- Efficiency: Larger props are inherently more efficient (Grams/Watt) because they accelerate a large mass of air slowly (low Disc Loading), rather than a small mass of air quickly.

3.2 Pitch

The theoretical distance the prop moves forward in one revolution.

- High Pitch (e.g., 5.1"): High Angle of Attack (AoA). Moves more air per revolution but stalls at low RPM (inefficient hover). Requires massive motor torque.

- Low Pitch (e.g., 3.0"): Low AoA. Spins up instantly (responsive) but "revs out" at top speed (the drone hits a wall of air resistance).

3.3 Moment of Inertia (MoI)

Often ignored, this is the most critical factor for PID tuning.

- Definition: Resistance to change in rotation.

MoI = sum(mass * radius^2). - Heavy Tips: A propeller with heavy blades or winglets has high MoI.

- The Control Loop: When the Flight Controller sends a command to "Stop Rolling," the motor must actively brake the propeller.

- High MoI: The prop keeps spinning due to momentum. The drone "overshoots" the angle, then bounces back. The pilot feels "slop."

- Low MoI: The prop stops instantly. The drone feels "locked in."

- Recommendation: Prioritize light-weight polycarbonate props over heavy glass-nylon blends for precision flight.

4. System Integration: Matching Motor to Propeller

The art of propulsion engineering lies in matching the motor's Torque-Speed curve to the propeller's Load curve.

4.1 Advance Ratio (J)

-

Static vs. Dynamic: On the bench, the air entering the prop is still (V=0). In flight, the air is moving.

-

Advance Ratio (J): The ratio of forward speed to tip speed.

J = Velocity / (RPM * Diameter) -

The Stall: As the drone flies faster, the effective angle of attack of the propeller decreases.

- Over-propping: If you put a high-pitch prop on a low-torque motor, the motor cannot reach the RPM needed to maintain a positive angle of attack at high speeds. The prop "unloads," and the drone stops accelerating.

- Under-propping: A low-pitch prop on a high-RPM motor acts as a speed governor. The drone hits its top speed instantly and wastes battery trying to spin faster against air drag.

5. Comprehensive Selection Guide

5" Freestyle (The Standard)

- Goal: Balance of power, response, and durability.

- Stator: 2306 or 2207.

- Kv (6S): 1750Kv - 1850Kv.

- Prop: 5x4.3x3 (Pitch 4.3). The "Goldilocks" prop.

5" Racing

- Goal: Maximum top end and cornering grip. Efficiency is irrelevant.

- Stator: 2207 (Tall) or 2208.

- Kv (6S): 1950Kv - 2100Kv.

- Prop: 5.1x5.1x3 (High Pitch). Requires high RPM to bite.

7" Long Range / Mountain Surfing

- Goal: Efficiency and Reliability.

- Stator: 2806.5 or 2807. (Large stator needed for torque).

- Kv (6S): 1300Kv. (Low Kv for Torque).

- Prop: 7x3.5x2 (Bi-Blade). Low pitch and low blade count maximize Grams/Watt.

3" Cinewhoop

- Goal: Lift heavy cameras (GoPro) in a small footprint.

- Stator: 1507 or 2004 (Wide/Flat).

- Kv (6S): 2800Kv - 3500Kv.

- Prop: 5-Blade (D76) or 3-Blade Ducted. High blade count needed to grab "dirty" air inside the ducts.

The "Prop Wash" Diagnostic

If your drone oscillates when descending into its own wake (prop wash):

- Physics: Your propeller's Moment of Inertia > Your Motor's Braking Torque.

- The Fix:

- Software: Increase D-Term (Active Braking) - Risky, heats motors.

- Hardware (Correct): Switch to a lighter propeller or a lower pitch. Or upgrade to a larger stator size (e.g., 2207 to 2306).

6. ArduPilot Integration: Key Parameters

How to tell the software about your propulsion choices.

MOT_THST_EXPO (Thrust Linearization)

- The Problem: Thrust is not linear. 50% throttle does not equal 50% thrust. (Thrust is proportional to RPM squared).

- The Fix: This parameter "flattens" the curve so the PID loop sees linear response.

- Setting:

- 5" Prop: ~0.65

- 10" Prop: ~0.60

- Large Props: Lower values.

- Tuning: If the drone oscillates at hover but is stable at high throttle, your Expo is wrong.

MOT_SPIN_ARM vs MOT_SPIN_MIN

- SPIN_ARM: The speed the motors spin when you arm the drone (on the ground). Set this low (e.g., 0.10) just to show the pilot it's live.

- SPIN_MIN: The "Air Mode" floor. ArduPilot will NEVER drop the motor speed below this value during flight, even at zero throttle.

- Why: If a motor stops in the air, the prop can desync or stall. This keeps the prop "biting" the air for stability during dives.

- Setting: usually 0.15 (15%).

MOT_BAT_VOLT_MAX / MOT_BAT_VOLT_MIN

- Voltage Scaling: As the battery drains (Voltage drops), the motors lose top-end power.

- The Feature: ArduPilot automatically scales the PID outputs. As voltage drops, it pushes the motors harder to achieve the same thrust.

- Requirement: You must set these parameters correctly (e.g., 25.2V Max, 21.0V Min for 6S) for the scaling to work.